Tree Swallow

General Description

Tree Swallows are elegant birds with white undersides, iridescent blue-green backs, and moderately forked tails. Seen in profile, this swallow has a sharp line of demarcation between the dark of the head above the eye and the pure white of the rest of the face and underparts. In Washington, Tree Swallows are most likely to be confused with Violet-green Swallows, but Violet-green Swallows have white patches extending up the sides of the rump that can be seen in flight. The white on the faces of Violet-green Swallows extends above their eyes. Male and female Tree Swallows in adult plumage look similar to each other, but Tree Swallows are unique in that first-year females, although reproductively mature, have a different plumage from older birds. This plumage is similar to the juvenile plumage--non-iridescent brownish-gray above with a grayish-white belly. Juveniles have a grayish breast-band that first-year females lack. Juveniles could be mistaken for Bank Swallows, but the breast-band of Bank Swallows is more distinct than that of juvenile Tree Swallows.

Habitat

When nesting, Tree Swallows are usually found near water. They require nest cavities, either natural or man-made. Often these cavities are situated over or immediately adjacent to water.

Behavior

This social bird is often found in flocks. Tree Swallows are highly acrobatic and forage mostly in flight, often swooping low over open water or fields, sometimes skimming food items from the water's surface.

Diet

Flying insects make up most of the Tree Swallow's diet, although more than any other Washington swallow, the Tree Swallow eats berries and other vegetative matter when insects aren't flying. This allows the Tree Swallow to weather cold spells better than other swallows, which in turn allows it to winter farther north.

Nesting

Tree Swallows are mainly monogamous, but extra-pair copulations are common. They nest in cavities--natural tree cavities, old woodpecker holes, or man-made nest boxes. Nests are located singly or in loose colonies. The male brings nesting material to the female, and she does most of the construction. The nest is a cup of grass, weeds, and other plant material, lined with feathers. The female incubates four to seven eggs for 14 to 15 days. Both parents feed the young, which leave the nest at 18 to 22 days. Parents continue to feed the young for at least three days after they leave the nest.

Migration Status

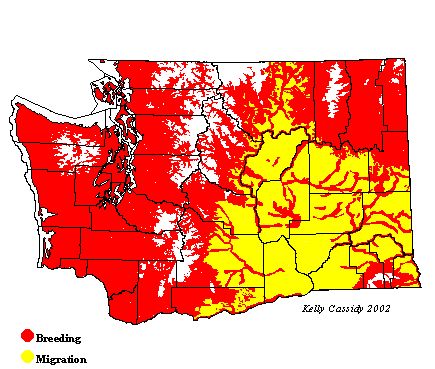

Tree Swallows are migrants, but do not migrate as far as other swallow species since they are not entirely dependent on flying insect prey. They migrate in loose flocks by day and gather in large groups to roost at night. They arrive in March, quite early in the spring. Most leave by mid-August, although a few can usually be found through September. Tree Swallows winter from North Carolina, the Gulf Coast, and Southern California to Cuba and Guatemala.

Conservation Status

According to Breeding Bird Survey data, Tree Swallows have increased (although not significantly) in Washington between 1980 and 2002. While the popularity of bluebird houses has provided many nest boxes for Tree Swallows, competition with European Starlings and House Sparrows for these and other cavities keeps the population in check. Relatively high levels of pesticides have been found in some western populations, and Tree Swallows are often used as indicator species for pollutants.

When and Where to Find in Washington

Tree Swallows are common in many open areas and wetlands throughout Washington from March through mid-August.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | R | C | C | C | C | C | R | |||||

| Puget Trough | R | U | C | C | C | C | F | U | R | |||

| North Cascades | R | F | C | C | C | U | R | R | ||||

| West Cascades | R | F | C | C | C | F | U | |||||

| East Cascades | U | F | C | C | C | C | C | R | ||||

| Okanogan | U | C | C | C | C | F | R | |||||

| Canadian Rockies | F | C | C | C | U | U | ||||||

| Blue Mountains | U | U | U | U | U | R | ||||||

| Columbia Plateau | F | C | C | C | C | F |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map