Common Raven

General Description

Common Ravens are large, black birds, with strong, heavy bills. They look rather like American Crows but are much larger and can weigh more than four times as much. When size isn't enough to distinguish the two species, look for the heavier bill and the shaggy feathers around the raven's throat. In flight, the raven shows a wedge-shaped tail from below, unlike the crow, which has a slightly rounded tail. Its wings are longer and less rounded, reminding one of a raptor. Ravens also typically soar and glide, while crows tend to flap continuously and fly in a direct path. Ravens are usually seen in pairs or small family groups rather than in the large flocks that crows often form.

Habitat

Common Ravens can be found in a wide variety of habitats. They inhabit dense forests, open sagebrush country, and alpine parklands. In Washington, they avoid cities but are common in cities in other areas. They prefer heavily contoured landscapes, perhaps because this type of habitat produces thermals that ravens use on their long-distance foraging trips.

Behavior

Common Ravens are most often found in pairs or in small groups, but they roost together in large groups in winter and large congregations may form at garbage dumps and other food bonanzas. Juveniles and non-breeders sometimes forage in small groups. They are very intelligent and sometimes cooperate to flush out prey when hunting. Ravens usually feed on the ground but will also feed in trees, often raiding other birds' nests. One of their many calls is a deep, distinctive croaking, often given in flight.

Diet

Common Ravens are omnivores, but most of their diet is meat. At times they eat arthropods, seeds, and grain, but they are more carnivorous than crows. They scavenge for carrion and garbage and also prey on rodents and on the eggs and nestlings of other birds.

Nesting

Common Ravens usually do not breed until they are 2-4 years old. They are monogamous and form long-term pair bonds. Pairs typically stay together year round, roosting near one another at night. Historically, they used cliffs and trees as nesting sites. Now power poles, bridges, and other man-made structures are commonly used. Nest sites are often re-used for many years. The nest usually consists of a base of large sticks woven into a bulky basket with a cup of smaller branches and twigs inside. The cup is then lined with mud, fur, bark, grass, and paper. The female (possibly with help from the male) incubates 3-7 (usually 5 or 6) eggs for about 20 days. The male feeds the female on the nest and helps her brood the young when they first hatch. The young leave the nest after 4-7 weeks. At this time, they can fly short distances and usually stay close to the nest for another week or so.

Migration Status

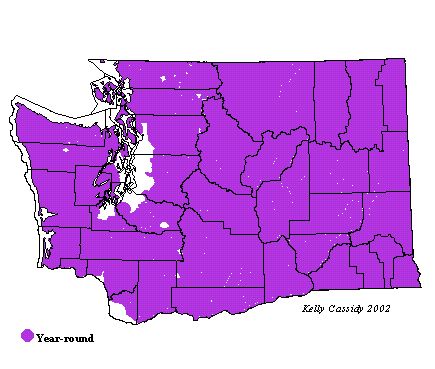

Common Ravens do not migrate, although some northern birds wander south in the fall and winter.

Conservation Status

Most western populations of the Common Raven have been stable for many years, but the population in the eastern portion of their range suffered a significant decline in the early 20th Century. Habitat loss, the loss of bison, the increase of crows, and human harassment all contributed to this decline. During the second half of the 20th Century, populations rebounded, and Common Ravens are returning to much of their former range. Ravens have been blamed for some of the decline of a number of species of concern, including California Condor, Marbled Murrelet, Least Tern, Snowy Plover, Sandhill Crane, and Sage Grouse, the eggs and young of all of which are preyed upon by Common Ravens. Some control measures have been proposed or are in place in some areas to try to reduce the ravens' impact. Common Ravens avoid cities in Washington, perhaps because of earlier harassment by humans, competition with increasingly abundant crows, and lack of appropriate nest sites.

When and Where to Find in Washington

Common Ravens are fairly common and widespread throughout the year in non-urban areas of Washington. They are generally absent from the developed corridor from Stanwood to Olympia (Snohomish-King-Pierce-Thurston Counties) and from the Vancouver (Clark County) area. They are most common east of the Cascade Crest but at times are common along Washington's outer coast.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F |

| Puget Trough | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F |

| North Cascades | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C |

| West Cascades | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C |

| East Cascades | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C |

| Okanogan | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C |

| Canadian Rockies | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C |

| Blue Mountains | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F |

| Columbia Plateau | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map

Family Members

Gray JayPerisoreus canadensis

Gray JayPerisoreus canadensis Steller's JayCyanocitta stelleri

Steller's JayCyanocitta stelleri Blue JayCyanocitta cristata

Blue JayCyanocitta cristata California Scrub-JayAphelocoma californica

California Scrub-JayAphelocoma californica Pinyon JayGymnorhinus cyanocephalus

Pinyon JayGymnorhinus cyanocephalus Clark's NutcrackerNucifraga columbiana

Clark's NutcrackerNucifraga columbiana Black-billed MagpiePica hudsonia

Black-billed MagpiePica hudsonia American CrowCorvus brachyrhynchos

American CrowCorvus brachyrhynchos Northwestern CrowCorvus caurinus

Northwestern CrowCorvus caurinus Common RavenCorvus corax

Common RavenCorvus corax